|

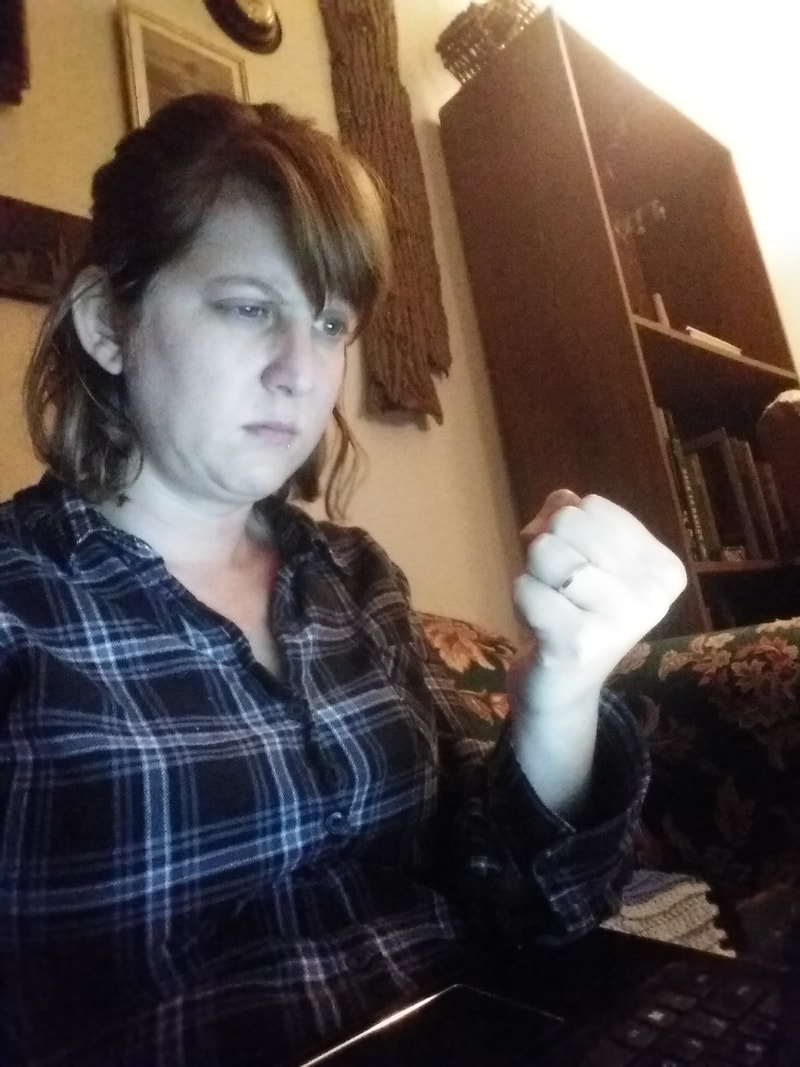

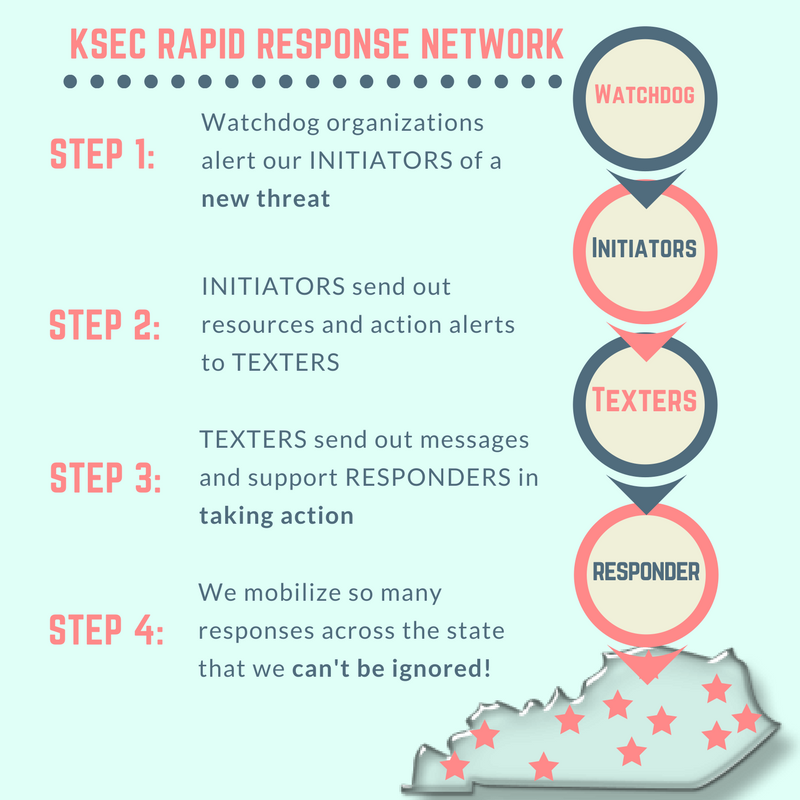

By Cara Cooper, KSEC Statewide Organizer It feels like I’ve been holding my breath a little bit since the 2016 election results. What will happen next? Where will the next threat hit us? It seems like there is no shortage of things happening to make me feel enraged. To be honest it’s been hard to keep up. The problem is that I can’t just become numb- decision makers need to hear from us. Often they only hear from paid lobbyists on the issues that impact us and even just mobilizing a few calls or letters can make a huge difference. We saw this earlier this year when KSEC and other solar advocates mobilized enough calls to Senator Carpenter that he pulled his bad solar bill off the docket. It can and has been done. And on top of that I know that is on our generation to step up and shape our vision for a just and sustainable Kentucky because we are inheriting the responsibility of protecting our communities and natural resources for our future and the future generations. We can’t let ourselves get overwhelmed or to give in to the feeling of powerlessness. The only way that we are going to win is if we stand together and show that we are powerful and united across the state. My face when I'm scrolling through all the bad news That is why we need a rapid response network. What if we had an easy way to identify the issues that we can have the most impact on, educate our friends about these issues across the state and mobilize dozens (or many, many more) responses as soon as a new threat arises? Now we can. Our new Rapid Response Network (RRN) is a peer-to-peer texting network that will allow us to connect with members across the state who have agreed to take action when we need it most. We’re partnering with watchdog organizations in Kentucky to quickly learn about new issues as they pop up and recruiting a team of texters and responders to get the word out and to take quick, strategic action. With the RRN we can mobilize quickly to show our unity and power like never before.

What does the RRN look like? Basically, watchdog organizations will alert a Rapid Response Network INITIATOR who will craft the action alert, gather resources and notify TEXTERS. Then our TEXTERS will send action alert text messages to our RESPONDERS using a peer-to-peer texting app called Relay and RESPONDERS will jump into action (anything ranging from making a phone call to the governor to submitting a letter to the editor to your local paper, to planning or attending a local vigil or rally). Don’t worry, TEXTERS will be there to support our RESPONDERS with resources and tools to make it easy. Read more about the roles here. When we work together and mobilize simultaneously across the state there is no doubt in my mind that we will blow the minds of our legislators and other decision makers with our coordination and power. We might not be able to stop every new threat to our environment but we sure as hell can make our voices heard. #ForOurFuture

In order for this plan to be successful we need committed people to sign up and for everyone to take action. You can sign up to be an INITIATOR, TEXTER or RESPONDER and someone will follow up with you to answer any questions you have before getting started. The actions we take (or don’t) really matter right now. Help us show that our generation is not apathetic and be a part of a real, tangible way to get your voice heard. Sign up now!

0 Comments

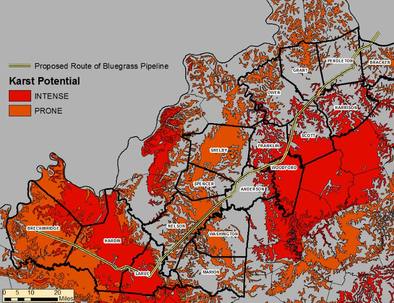

By Cameron Baller: UK Greenthumb, Just Transition Working Group Steering Committee, Pipelines and Natural Gas Working Group The 2016 presidential election threw every federal agency for a spin, few more so than the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). A little known agency, the FERC is responsible for regulating nuclear energy and oil and gas pipeline infrastructure, among other things. After Donald Trump was elected, members of the FERC leadership quit abruptly, leaving the agency without enough administrators to make decisions. They had been stuck in limbo, stalling all new regulations and decisions about pipelines. This purgatory is where the Kinder Morgan Pipeline project has been for the past few months… but no longer. This dangerous pipeline project is lurking under our radar and it is critical that we prepare now so that we can stop it in its tracks. Read on for more information and to learn how to join us in stopping this pipeline.  Not Kentucky’s First Rodeo There is a storied legacy of companies trying to snake dangerous pipeline infrastructure through Kentucky. In 2013, the Williams and Boardwalk Pipeline Partners proposed the Bluegrass Pipeline. In an effort to intimidate landowners into selling their land for the construction of the pipeline, the company told landowners that it would use eminent domain to take their land for the project, which would be a bad financial deal for the landowners. A broad array of constituents came together, including landowners, advocacy groups, policymakers, and even a group of singing nuns to fight the project. Several landowners formed a blockade, refusing to sell their land to the pipeline company, while other allies pursued legal action. In 2015, the Kentucky court system determined that the Bluegrass Pipeline could not use eminent domain to seize land for the project, functionally stopping the pipeline. The court ruling hinged on a key fact: the pipeline was carrying natural gas liquids (NGLs) and NOT natural gas. NGLs are not methane and are not used primarily for energy. They are co-products that are obtained, along with methane, from the natural gas extraction process. Rather than being used for heat and power, they are used as inputs for plastics and chemical manufacturing. This distinction was critical in the court’s eminent domain decision. Another important distinction between NGLs and natural gas is that NGLs vaporize and, because of their relative weight, displace the air. In simple terms, this means that when an NGL pipeline leaks, the vapors could suffocate anyone and everyone within the leak area.  Credit: Kentuckians For The Commonwealth Credit: Kentuckians For The Commonwealth A New Pipeline Waiting to Strike Not long after the Bluegrass Pipeline was defeated, Kinder Morgan began exploring their own NGL pipeline project. This time, the dangers are even more severe. The Tennessee Gas Pipeline is owned by a subsidiary of Kinder Morgan and has carried actual natural gas from South to North for over 70 years. Now, Kinder Morgan hopes to “abandon” this pipeline (to do so, it must first get the approval from the FERC) and then sell the pipeline to another one of its subsidiaries, the Utica-Marcellus Texas Pipeline (UMTP). UMTP would re-purpose the pipeline, flip the flow so that it goes from North to South, and send NGLs along the pipeline instead of natural gas. There are a few important reasons this project is even more dangerous than the Bluegrass Pipeline. The existing pipeline is more than 70 years old, therefore subject to the normal wear and tear that 70 years of use will bring, and no longer meets today’s pipeline construction safety standards. In an area with geology as dangerous as Kentucky’s infamous karst, where sinkholes gobble up several Corvettes at a time, it is terrifying to think that we are considering transporting dangerous NGLs by pipeline, let alone transporting them through a pipeline so old and out of standard. Furthermore, they are both flipping the flow of the pipeline and sending new materials down it, these are both stressors that the pipeline has not been subjected to and could present unpredictable problems and an increased risk of leaks. Finally, Kinder Morgan observed and learned from the Bluegrass Pipeline fight. In re-purposing an existing pipeline, they may be able to utilize the existing land easements, circumventing the need for eminent domain. These tactics go against the clear demands of Kentuckians and require new and creative strategies in response. Re-organizing in the New Landscape

In August, the FERC regained quorum after Trump appointed new commissioners to the agency. Given the political leanings of these appointees, we should not be surprised when they approve Kinder Morgan’s request to “abandon-in-place,” functionally granting the company a blank check to do the re-purposing. As the official comment period is over, and the die seem to be cast in terms of the FERC, it seems like the most important action now would be to prepare for that announcement and get out ahead of it. The good news is we are not beginning from scratch. Organizations across Kentucky have been working on this issue since the beginning, including the Kentucky Resources Council (KRC), Kentucky Heartwood, Kentuckians for the Commonwealth (KFTC), the Kentucky Environmental Foundation, among others. However, organizing efforts have stalled as the FERC lost its ability to make decisions. It is essential that we now re-energize resistance efforts before it is too late. With that goal in mind, the Kentucky Student Environmental Coalition (KSEC) has created a new Pipelines and Natural Gas Working Group (PNWG), which is focused on stopping the Kinder Morgan Pipeline project. We plan to work with other state and campus organizations, local communities and government officials to create a multi-layered resistance effort sufficient to block the project. We cannot hope to tackle this issue alone. Following the lead of the Bluegrass Pipeline resistance movement, we hope be a part of creating a diverse resistance movement across the state that can demonstrate a unified voice against the pipeline. We are more powerful than Kinder Morgan, but only together. In the coming weeks and months, we will be reaching out to a variety of stakeholders and developing tactics that allow everyone to be a part of this resistance. For now, informing yourself on this issue and preparing to become a part of the response effort are critical. We will fight for our future and we will no longer be ignored. By DeBraun Thomas, Take Back Cheapside I have long been a student of history. I’ve always been fascinated by the way others have overcome obstacles I’ve never had to face. Learning how things came to be and what can come from experiences of the past has inspired me to continue researching and exploring history. Sometimes, the past can seem much farther away than it actually is and in a way, we can become desensitized to atrocities of the past. When it comes to the continued fight against oppression, our understanding of the present should be placed within the context of historical perspective. I was born on March 3rd 1989. George HW Bush was President of the United States and the country was entering yet another phase in history. I was born 126 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, 35 years after the murder of Emmett Till and the decision of Brown v. Board of Education, 24 years after the passing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 21 years after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., 20 years after the assassination of Fred Hampton and 20 years after Apollo 11. Yes, you read that correctly, I was born only 20 years after the moon landing. I am the great grandson of a slave and I’m only 28 years old.

I moved from Menlo Park, California to Lexington in 2008 to attend the University of Kentucky. As I met more people from the city and my social circles bubbled outside of the university, I started learning about Lexington’s history. While much of Lexington’s landscape has changed, many things considered “tradition” have stayed the same. One of the many places in Lexington that has not changed very much is the space downtown known as Cheapside. Since the inception of the city in 1782, the space has been used as a marketplace. To clear up any misconceptions, the name Cheapside comes from Old English. Ceap in Old English means “to buy” and side means “place,” therefore the name literally means marketplace. Between 1830 and 1865, Cheapside was home to the second largest slave auction site in the country. In 1887, 22 years after the Civil War ended, a statue was erected of John C. Breckinridge, Secretary of War for the Confederacy. In 1911, 46 years after the Civil War ended, there was a statue erected of John Hunt Morgan, a Confederate General. Both of these men defected to the Confederacy and both of them were slave owners who fought to uphold the institution of slavery. Their statues stood at Cheapside with no telling of history of the space as a slave market until 2003, when Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity placed a historical marker to memorialize the marketplace’s past. After George Zimmerman was found not guilty in the murder trial of Trayvon Martin in 2013, a conversation about racial justice began sweeping across the nation. In 2015, this conversation descended to Lexington, causing many to look within their own community. Part of this conversation was around the statues still standing at Cheapside. That year, someone spray painted “Black Lives Matter” on the statue of John Hunt Morgan and the historical marker was knocked down and broken. This prompted Mayor Gray to request to the Urban County Arts Review Board (UCARB), a group of appointed individuals who discuss the placement and/or removal of art in public spaces, to give a recommendation on what to do with Cheapside. I attended two public discussions on the issue. The first was a town hall meeting at the Carnegie Center. In the room were members of the Klan and supporters of the Confederacy. The tension was high, but in that moment, I felt that the voices of the oppressed were actually being heard. The second meeting was held at City Hall in front the UCARB. I was the youngest person in the room except for the two little girls of a man who was adamant about keeping the statues for fear of the “erasure of history.” In July of 2016, Philando Castile and Alton Sterling were both killed by police officers. Both murders were captured on video and in both cases each of these men were doing nothing to warrant losing their lives. I was angry and frustrated that, in 2016, these issues were still happening and that I found myself continuing to have to explain and justify the phrase “black lives matter” to individuals lacking in melanin. In death, Castile and Sterling inspired me to channel my anger and frustration into constructive action; the result was Take Back Cheapside, a movement to remove the two confederate statues from Cheapside Park and commemorate Lexington’s black history. I believe that we as people can have the most success fighting oppression by understanding each other’s individual struggles and by standing together. These values are at the heart of Take Back Cheapside. This blog post was originally scheduled to go online on Monday, August 14th. All of those plans changed after the events in Charlottesville on August 12th. It is a day I will never forget and a day that changed my life. Many different people across the country came out to make statements about what had happened. I was struck with so much grief and I will never forget the name Heather Hyer the same way I will never forget Emmett Till. I was still trying to process all that happened when I got a phone call from someone in City Government who told me they had heard that the mayor of Lexington, Jim Gray, was going to announce plans to move the Confederate statues at Cheapside at the city council meeting that Tuesday. It was a bittersweet moment because it came on the heels of Charlottesville, but I found solace in the fact that we could move forward with this work in a way that had the support of city officials. Once the mayor’s plan was made public, I immediately started planning for what was to come, well, and then I went and got a burrito (because eating is important). Later that evening Mayor Gray released a video statement on Facebook. All of the conversation up to this point had highlighted the statues and not the space itself. That’s why, after watching the video statement, I was relieved and confident that the mayor was moving forward with his efforts to relocate the statues for the right reason. Towards the end of the video, Mayor Gray said “the statues that stand on our old courthouse lawn today also stand on sacred ground, the Cheapside auction block” he then goes on to say “So let’s think about it, it’s just not right we would continue to honor these Confederate men who fought to preserve slavery on the same ground as men, women, and even children were once sold into a life of slavery. Relocating these statues and explaining them is the right thing to do.” So, what do these recent events mean for the campaign? Well, we are very close to where we want to be, but still have a long way to go. The conversation about moving confederate monuments was thrust even more into the spotlight and in the same way people used their voices to try to silence us, many others in this city used theirs to join us. On August 17th, after hearing from members of the community for 3 hours, the city council voted unanimously to give the city 30 days to find a new location for the statues. Once they find a new location and confirm it, then the city can send their petition to the Kentucky Military & Heritage Commission. That commission meets in November and if they vote in our favor, the statues will be relocated. My life has been extremely stressful since August 13th. I have received threats to my life, have needed to stay at other people’s homes, and everywhere I go, I am looking over my shoulder. While it puts a strain on every aspect of my life, it is a burden I’m willing to bear because others, like the 19th century abolitionists and 20th century civil rights leaders, did the same for me. So, that being said, I’d like for you to read the last few paragraphs of what I originally had written for this blog post (before Charlottesville) because the solidarity I wanted for this city was exemplified at the city council work session on August 15th and at the city council meeting on August 17th and has continued to be exhibited by all of the other organizing groups that have come to aide Take Back Cheapside. The room was overflowing with people, so much so that on Thursday, people were lined up outside the government building and were also watching the meeting at other businesses downtown. The police Chief the other day told me that it was the most people he’s seen at a city council meeting in his 30 years on the force. That is not just what democracy looks like, but what solidarity is. Fred Hampton, a leader of the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party, embodied solidarity and once said, “you don’t fight fire with fire, you fight fire with water. We’re gonna fight racism not with racism, but we’re gonna fight racism with solidarity.” Merriam Webster’s dictionary defines solidarity as “unity (as of a group or class) that produces or is based on community interests, objectives and standards.” Many of the people who pushed the Civil Rights Movement forward were young people, college students, friends and peers who stood together for something greater than themselves. In the annals of history, they are viewed as larger than life, but in reality, they were just everyday people. Fred Hampton was an ordinary college student who brought a much-needed spark the to the movement for his generation and now is the time we provide the spark for ours. I am writing about the oppression of people of color on an environmental blog for the very definition of solidarity. The movements for racial justice and environmental protection are deeply connected. Every movement that struggles for justice, from the labor movement to the feminist movement and everything in between, is connected in their resistance of the same oppressive systems and power structures. Only when these movements stand together in solidarity will any of them truly win. I think that a quote from 1971 by Funkadelic speaks to this very ideal: “Freedom is being free of the need to be free.” Take Back Cheapside is co-hosting a Panel On Solidarity with the Kentucky Student Environmental Coalition to further explore how our respective movements for racial justice and environmental protection are connected and can stand together. I hope you’ll join us at the Carnegie Center on September 27 from 5:00 to 7:00 p.m. to learn more about Take Back Cheapside and Lexington’s forgotten history of people of color, the work KSEC is doing to build a just and environmentally sustainable Kentucky, the systems of oppression that connect our movements, and why it’s important that our two organizations support one another. We hope to inspire others to work together in solidarity. Step up and be the change you wish to see in the world so that one day others can have a chance to be successful because you fought for them. We can work towards that day by standing together and by fighting every single day to give All Power To The People. By Ivy Brashear, Appalachian Transition and Communications Associate at MACED  Ivy Ivy Della Combs Brashear had had enough. She backed her Cadillac long-ways across the road in front of her house, lit the Virginia Slim in her mouth, pulled her .38 pistol from her purse, and waited, stone-faced and determined, for the next coal truck to come along. The trucks had been running day and night up and down the road in front of her house every day for weeks, coating every bit of furniture in and outside her home with a thick layer of grey coal dust. There’s only so many times a woman bound to the code of Clorox can clean up after someone else’s mess before the time comes to act. She wasn’t afraid of jail – “They’ll give me three hot meals a day and a place to sleep!” – she was more interested in defending her home from unwanted intrusions. Fierce is a good word for Della Combs: Fiercely loyal to her children and grandchildren. Fierce advocate for doing unto others as you would have them do unto you. Fierce mountain woman who had big dreams of city life, playing piano and singing in Chicago or New York City, but who instead married a man her mother wanted her to before graduating high school, and stayed with him until the end of her life because of a fierce sense of duty. To me, though, she was Granny Della – fierce storyteller who had the most enormous zest for life and love, with the heart to match. Her laugh seemed to always echo off of the walls and reverberate off of the hills that held the holler. It could fill you up, that laugh, and shake off your troubles for you. She always wore lipstick and powder, and had arthritis in her toes from a youth spent in high heels. She maintained a standing hair appointment every Friday at Dascum’s in Vicco, and earned her GED when she was in her 40s. Her door was always open to me, and since I lived just up the hill from her, I was often in her kitchen as she put up peaches in Ziploc bags for winter, or watered her beloved hanging ferns that encased her porch. She played piano every Sunday at Lone Pine Baptist Church – the family church founded by my great-grandfather, less than a mile from my home. When she told me I had “piano fingers,” I felt so special, like she had chosen me to carry on her music.  Della and Ivy Della and Ivy She was gregarious and out-spoken, once telling a man to “get a life and get a job,” another time telling Lone Pine’s preacher that he was wrong about God not giving people talent they didn’t have to learn. But I would never – in my wildest dreams or imaginings – disrespect her by calling her a lunatic, as J.D. Vance so often refers to his Mamaw in “Hillbilly Elegy.” The fact that people will read his book, and assume that all Appalachian people are trying to actively run away from their culture, and that if they are smart, they will understand it to be less than and the people they came from to be crazy lunatics is, to me, one of the more personal attacks that Vance hurls at Appalachian people in his 261-page simultaneous fetishization and admonishment of my culture. "Elegy" has no class, no heart, and no warmth. It's a poorly written appropriation of Appalachian stereotypes that presents us as a people who aren't worthy of anything but derision and pity, and who cannot be helped because we refuse to help ourselves. It ignores the systemic capitalist oppression that encourages persistent poverty. It assumes there is some special sect of the working class that is especially dedicated to white people. It is rife with fragile masculinity that actively diminishes the critical role that Appalachian women play in the culture, the resistance, in the workforce, and in the new economy. I come from dignity and grace and laughter and joy, and while I do not discount the difficult childhood that Vance lived through and his own lived experience, "Hillbilly Elegy" erases and erodes any Appalachian experience outside his own non-Appalachian experience by reinforcing repeatedly that Appalachian “hillbilly” culture is somehow deficient and morally decrepit, and that it is something to be overcome. Misrepresentation of Appalachia matters for several reasons. It obscures and intentionally eclipses the pride and dignity of being Appalachian. It has told us we should be ashamed of who we are, where we come from, and the people in our blood. It says to us that we aren't worthy or deserving of anything more than being the butt of a joke. It hits us hard in our guts because the truth is way more complicated and way more real, and nobody likes tales to be carried about them. But I think the thing that bothers me most is this: Appalachian misrepresentation actively and intentionally ignores and excludes the real life, lived experiences of all but a minority of Appalachian people. It ignores my fierce Granny Della. It ignores my Granny Hazel, who smelled of starch and taught me how to feed the chickens and always had breakfast waiting on me when I had to stay with her on a sick day. Misrepresentation certainly doesn't tell the stories of my Grandpa Earl, who liberated concentration camps, who referred to me exclusively by my middle name, Jude, and who always had a Werther's candy ready for me. My Mom and Dad are left out. They owned a gas station that hired local high school kids. They hung Modigliani and Van Gogh and Paolo Solari prints on the walls of our home. They played NPR every Sunday morning. They fought the dam at Red River Gorge, the racists in Hazard, the strip mining companies for which Dad used to work, and they both went back to school later in life and got degrees. It ignores me: a young, queer Appalachian with roots ten-generations deep in eastern Kentucky, who holds within me the fierce loyalty and determination of my Granny Della, the unconditional compassion of my Granny Hazel, the individuality of my parents, and the mountain heart and soul of all my ancestors combined. My family is totally, completely, utterly left out and ignored, and so are the families of so many other Appalachians that are just like mine. We are Appalachian, too, but in “Hillbilly Elegy,” and so many other representations and think-pieces like it, we are cast aside for the lies we tell ourselves about the mythical other and perceived, inherent difference. “Hillbilly Elegy’s” danger is that it continues the long tradition of understanding and presenting Appalachia as a monolithic region and group of people. For those of us who are trying to shift the narrative of our place to be more honest and complex as a way to support just economic transition, facing mass-market, much devoured and incomplete narratives like “Hillbilly Elegy” is akin to mining coal with a pick ax. Ivy originally presented this essay on a panel discussion about "Hillbilly Elegy" at the 2017 Appalachian Studies Association Conference at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Virginia. Bio: Ivy Brashear is the Appalachian Transition and Communications Associate at the Mountain Association for Community Economic Development in Berea, Ky. Before joining MACED, she was a reporter at the Hazard Herald in Hazard, Ky. She currently sits on the New Economy Coalition board of directors, is on the steering committee of the Kentucky Rural-Urban Exchange, and is a member of the Young Climate Leaders Network. She holds a Bachelor’s degree from Eastern Kentucky University in Journalism and Appalachian Studies, and a Master’s degree from the University of Kentucky in Community and Leadership Development. She is a tenth-generation Appalachian, and a fifth-generation eastern Kentuckian, where her family still lives on land settled by her great-great grandfather in the 1830s.

By Cara Cooper, KSEC Organizer

Events and actions also took place at Morehead State University where their newly revived environmental club Environmental Eagles screened the documentary Dam Nation (Kentucky has dams on many of our waterways at a great detriment to the natural environment), and at Northern Kentucky University.

Beginning with Kentucky's campus communities, KSEC works toward an ecologically sustainable future through the coalescence, empowerment, and organization of the student environmental movement. We are a unified front moving forward on environmental justice through activism, development, and education. We believe in holding campuses, corporations, and governments both responsible and accountable not only in maintaining the environment but allowing ecosystems to live and prosper. We seek to expand our reach and engage our communities by building relationships with non-student driven organizations which stand in solidarity with our cause. By using our unique position as students, we demand that our universities practice sustainability by utilizing clean, renewable, safe energy. |

AboutThe Young Kentuckian is a blog of the Kentucky Student Environmental Coalition where youth share their work and ideas for Kentucky's bright future. Follow The Young Kentuckian on Facebook!

Categories

All

Archives

March 2023

|